What’s the difference between PTSD and C-PTSD?

December 3rd, 2025

Summary

Psychological trauma impacts many Australians. The effects can often go unnoticed by the public because the symptoms are not always immediately obvious to others. The symptoms typically impact a person’s perception of themselves and the world, and the impacts can be experienced at work, home, and personal relationships.

It’s estimated that 75% of Australian adults will experience a traumatic event in their lifetime, while 11% may go on to experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Complex PTSD (C-PTSD), although less researched than conventional PTSD, is believed to impact 4% of Australians.

What constitutes PTSD versus C-PTSD often confuses people. This is understandable because C-PTSD was not officially defined until 2018. This article aims to outline the differences between PTSD and C-PTSD symptoms, followed by discussing how the conditions are diagnosed and the available treatment pathways.

So, what is PTSD?

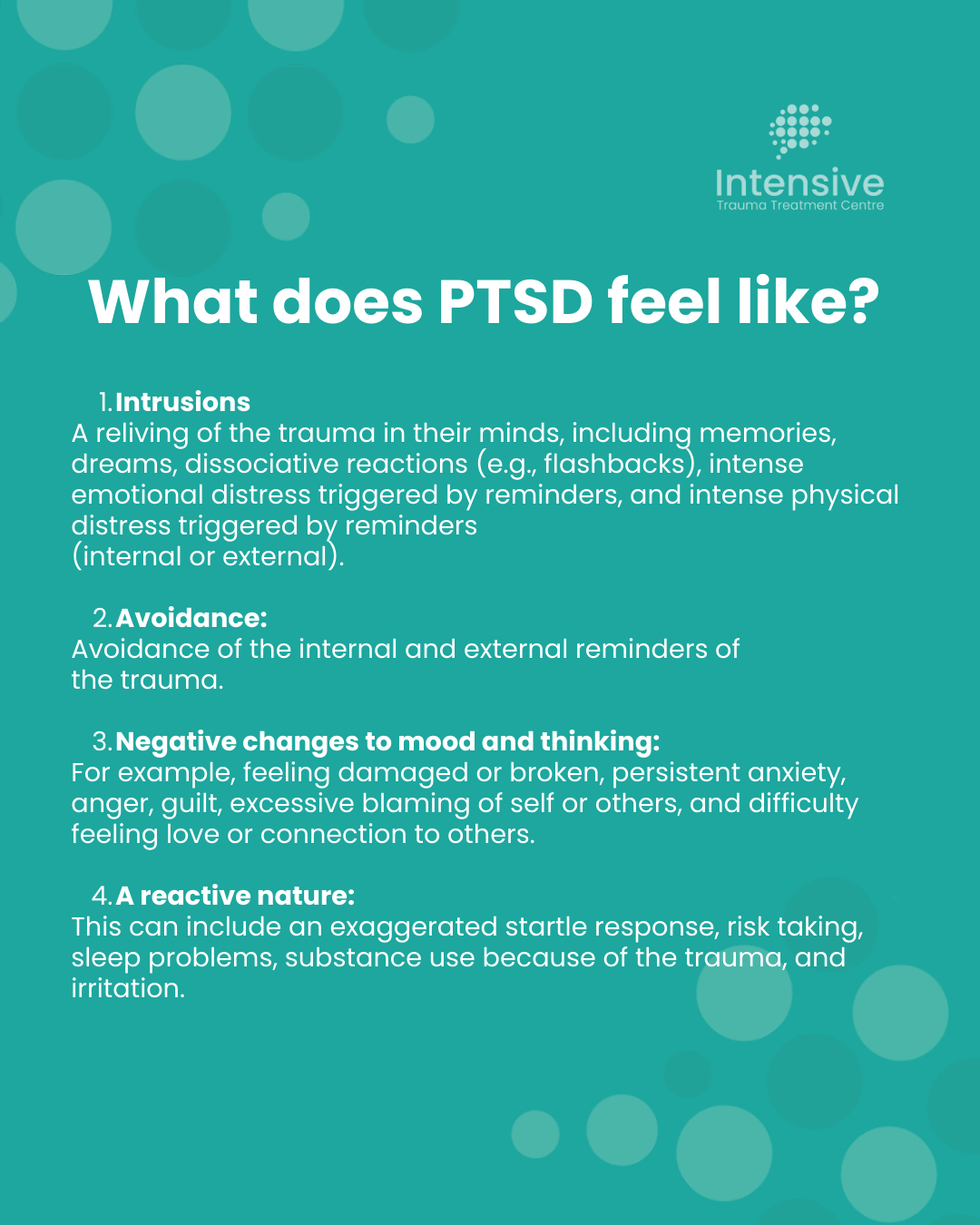

PTSD is the development of certain symptoms following exposure to one or more traumatic events.

Trauma is defined as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. It can be experienced directly, witnessed by another, or learned about as happening to a close family member or friend.

Some negative life experiences can cause PTSD-like symptoms, but the event might not fit the definition of a ‘trauma.’ For example, discovering a partner’s affair, bankruptcy, and bullying can be traumatic and therefore cause the same or similar symptoms to PTSD despite not technically being a ‘trauma.’

People will often be diagnosed with Adjustment Disorder if the symptoms are caused by negative life events that do not meet the official definition of trauma.

How is PTSD diagnosed?

PTSD is typically diagnosed in a therapeutic setting, such as with a GP, Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Paediatrician, and/or mental health team. The primary assessment method is a ‘Clinical Interview’ or ‘Consultation’. A clinical interview is a discussion about the patient’s personal history and current symptoms, such as when the symptoms started, what makes the symptoms better or worse, and how the symptoms affect everyday life. The discussion can be in person or via telehealth.

Some doctors might check for medical conditions that could be contributing to the symptoms, such as requesting blood tests to check for thyroid problems. Some psychologists will use questionnaires to evaluate the range and severity of symptoms.

Throughout the diagnostic process, the health professional will consider whether other factors are causing or contributing to the symptoms. This is important because an accurate diagnosis is critical to developing an accurate treatment plan. For example, OCD and PTSD can sometimes look similar. Both conditions can feature intrusive and distressing thoughts about personal safety, avoidant behaviour, and significant anxiety. Despite looking similar, how the conditions are treated can be extremely different, so an accurate diagnosis is essential.

Finally, a diagnosis can only be made if the symptoms persist for more than one month, and the symptoms cause significant distress and/or interference in everyday functioning.

What is C-PTSD?

C-PTSD was officially defined by the World Health Organisation in 2018. It includes the core symptoms of PTSD but adds three additional considerations. These are called Disturbances in Self-Organisation (DSO).

Symptoms of DSO include:

- Emotional Dysregulation: Difficulty managing emotional responses, such as intense anger or emotional numbness.

- Negative self-concept: Persistent beliefs of being worthless, shameful, or damaged.

- Disturbances in relationships: Difficulties in forming or maintaining close relationships or feeling disconnected from others.

C-PTSD is usually linked to long-term trauma that was difficult to escape, such as repeated exposure to childhood abuse (e.g., domestic violence, institutional sexual abuse), neglect, and/or being held hostage (Herman, 1992; Cloitre et al., 2013).

How is C-PTSD Diagnosed?

C-PTSD is diagnosed the same way as PTSD. That is, the patient discusses their symptoms with an appropriate healthcare provider in-person or via telehealth. The healthcare provider might also request medical tests and/or psychological testing to rule out other causes of the symptoms.

The diagnosing healthcare provider will often consider whether the person also has personality difficulties, such as borderline personality disorder (Resick et al., 2012). This is because the conditions can look very similar and sometimes co-exist. Diagnosing mental health conditions can be complex, because certain difficulties, such as post-traumatic symptoms and challenging personality-related patterns, can overlap or occur together. Experienced clinicians carefully consider these factors to ensure an accurate understanding of each person’s situation. This thorough process reflects the clinician’s training and judgment; mental health diagnoses are best based on clinical evaluation rather than a single medical test.

PTSD vs C‑PTSD: Comparison Table

| Feature | PTSD | C-PTSD |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma Type | Usually single or short-term traumatic events. | Often prolonged or repeated trauma, usually with an interpersonal element and was difficult to escape. |

| Core Symptoms | Intrusive and distressing memories, avoidance, hyperarousal. | All PTSD symptoms plus Disturbance in Self-Organisation (DSO), symptoms such as emotional dysregulation and relationship difficulties. |

| Emotional Regulation | May be intact or disrupted. Emotion dysregulation may be context specific (e.g., in situations that resemble the trauma) rather than pervasive across contexts. | Core symptom of C-PTSD. Often significantly impaired across contexts. |

| Self-Perception | May not “feel themselves”, such as feeling broken or damaged. Strong feelings of guilt, shame, and/or anger may be present. | A severe negative self-concept, such as feeling worthless and having a shattered sense of self. The person might feel that they have lost a sense of who they are (i.e., major identity disruption). |

.png)

Mnemophobia and Avoidance: The Essential Treatment Targets

After trauma, the brain might mistakenly learn that the trauma memory itself is dangerous. This is because thinking about the experience provokes strong, upsetting emotional and physical reactions. This can be to the extent that people with PTSD and C-PTSD might feel like they are reliving what happened.

Additionally, the memory might not be properly processed by the brain. This is for a couple reasons.

- First, there can often be a flood of hormones and neurotransmitters at the time of a traumatic experience. Those chemicals are helpful to activate the fight, flight, freeze, fawn response, but too much of those hormones can interferes with the brain’s information processing system. The brain’s primary information processing system is called the hippocampus.

- Second, the brain is usually very busy processing information in the hippocampus during REM sleep. This is when we dream. Unfortunately, many people with unresolved traumatic memories have hormone and neurotransmitter release during REM sleep that wake while the brain is trying to process the trauma. This interferes with the brain’s opportunity to process the unresolved information (e.g., images, sounds, emotions, sensations, and beliefs about the trauma).

The person is then left with distressing memories that the brain is struggling to process.

This leads to mnemophobia – a fear of memories. A fear of memories is a hallmark of PTSD and C-PTSD. Many people cope with their fear of trauma memories with avoidance.

Avoidance

Avoidance is another hallmark symptom of PTSD and C-PTSD. It can take the form of avoiding people, places, conversations topics, smells, emotions, and sensations, among others.

Some people avoid feeling relaxed because feeling relaxed triggers a sense of unsafety. This is why some people with PTSD and C-PTSD struggle with relaxation strategies- it triggers the core PTSD symptoms!

However, some people find relaxation activities extremely useful for their symptom management. So people might keep themselves extremely busy with gaming, working, eating, sleeping, sex or other activities. This is so their mind is always busy and therefore there is limited space for the trauma memories to intrude.

Problematically, avoidance maintains the mnemophobia. It prevents the brain from learning that the memory, while painful, isn’t a threat anymore. It disrupts opportunities to ‘unfreeze’ the memory from being stuck on the worst part, and it interferes with the brains opportunity to learn that the traumatic experience is over now.

The Road to Recovery

Psychological techniques like Exposure Therapy and EMDR can help change the brain whilst addressing avoidant behaviour. Through repeated exposure to the memory with the safe guidance of a qualified therapist, the brain reprocesses the memory without avoidance interrupting the opportunity. Mnemophobia and avoidance are tackled at the same time, with the added benefit of now being able to think about the trauma differently and ideally without the intrusions. The person learns that they can control the memory, rather than it controlling them.

It is often noted that trauma recovery is difficult and long, however there are faster solutions out there. For example, if a loved one had a fear of spiders or birds, would you tell them to only face the fear once per week or month? Probably not. You would encourage them to ‘get in and get it done quickly’ so they can move on with their life sooner.

That is how the ITTC treats PTSD and C-PTSD. We provide a high number of prolonged exposure and EMDR sessions in a short timeframe (e.g., 4 days) with the aim of facilitating rapid recovery.

If progress is too slow, which is known to occur in weekly, fortnightly or monthly sessions, then the person may dropout of therapy or the therapy becomes derailed by managing the symptoms (e.g., with relaxation strategies) rather than directly treating the symptoms with first line therapeutic technique.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th revised ed.).

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., & Maercker, A. (2013). Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 20706.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

- Phoenix Australia (2021). Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex PTSD. Phoenix Australia.

- Resick, P. A., Bovin, M. J., Calloway, A. L., Dick, A. M., King, M. W., Mitchell, K. S., ... & Wolf, E. J. (2012). A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: Implications for DSM-5. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 241–251.

- World Health Organisation. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (11th ed.).